Raymundo Andrade

Works & Biography

About Raymundo Andrade

Born in 1961, Tepic, Nayarit, Mexico.

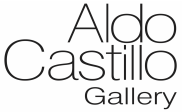

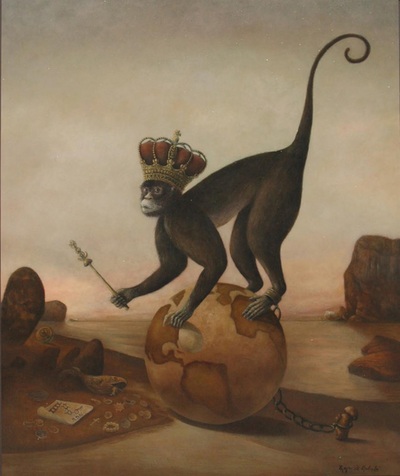

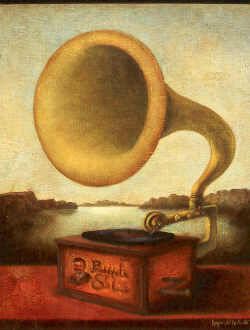

A Doctor in medicine and a Doctor in letters and history, Raymundo Andrade fuses a unique academic background with his art. His canvases are veiled in a delicate sense of nostalgia, and warm muted tones seem to further suspend his images in timeless reverie. His works clearly pay tribute to both the natIve and Spanish cultures that are such a part of Mexico’s vast cultural history. Spiritual, cultural, and natural richness and fertility are themes that pervade the themes of this artist. His works have been exhibited extensively in California, Arizona, Washington, and Mexico.

A physician, philosopher, and artist with an extensive background of exhibitions in Mexico, the U.S., and Canada.

“I don’t like making statements about my work, because I don’t paint with a concept or a story as a starting point. I start with an image, so it is sometimes difficult to put into words. They (my paintings) are images that I like, it’s like the sunset, it’s something that strikes you.”

Raymundo appears to be a man drawn to the great mysteries of the human condition. His motivations and themes lead Raymundo to follow the school of the great masters. “If I used a brighter palette, or a hyper-realistic approach, my paintings wouldn’t come across the same”

RAYMUNDO ANDRADE

WITTE MUSEUM USA

San Antonio, .TX USA

MySA San Antonio´s Home page web Escrito por Steve Bennet

“Miradas” runs through Aug. 21 at the Witte Museum, 3801 Broadway.Arts & Culture

'Miradas' reveals how Mexican artists confronted modernity after Revolution

By Steve Bennett [email protected]

Javier Chavira's painting "El guerrero (The Warrior)" is featured in "Miradas: Mexican Art From the Bank of America Collection," a survey of 80 years of Mexican art since the revolution.

The Witte Museum marked the centennial of the Mexican Revolution last year with its multifaceted exhibition “1910: A Revolution Across Borders.” Now the venerable institution examines the artistic legacy of that earth-shattering rip in society's fabric with a seismic summer show that traces the development of Mexican art over the past 80 years in some 100 works.

“Miradas: Mexican Art From the Bank of America Collection” features paintings, prints and photography by 32 artists, including Diego Rivera, Manuel Alvarez Bravo, Graciela Iturbide and Rufino Tamayo, as well as contemporary artists such as Alejandro Colunga, Judithe Hernandez and Luis Jiménez.

“The ‘Revolution' show was very gritty,” says Marise McDermott, Witte president. “It really captured the violence of those times. This one explores the explosion of art across the U.S.-Mexico border.”

According to Cesáreo Moreno, chief curator and visual director at the National Museum of Mexican Art in Chicago, a furor of post-Revolution nationalism fueled the engines of creativity as Mexican artists rediscovered their country's past and peered ahead into its future.

“At the close of the war, an era of peace was ushered in gradually, with a different political order, a strong sense of nationalism — known as Mexicanidad (Mexican-ness) — and newfound social goals,” says Moreno, organizer of “Miradas,” a touring show culled from one of the country's strongest corporate collections. “Artists sought to develop an artistic language that could convey their sense of modernity in an increasingly industrialized world.”

Among the outlets of expression was a cultural movement known as Indigenismo (Indigenism or Indianism), Moreno says, pointing to “Miradas” paintings by Jean Charlot, a Zapotec mestizo born in Paris in 1898, and Guatemala native Carlos Mérida's series of lithographs reimagining the creation myths of the Popol Vuh.

“Artists and writers who participated in this movement explored their national heritage and proudly included in their work aspects of ancient Mesoamerican culture,” he says.

The Mexican mural movement emerged from the Revolution as well, and Los Tres Grandes (The Three Giants) — Diego Rivera, José Clemente Orozco and David Alfaro Siqueiros — became Mexico's artistic ambassadors, global beacons who championed indigenous culture and the rights of the common man, even as they adopted and adapted international avant garde theories and methods.

Although a meditative suite of later (1968) Siqueiros lithographs dealing with family (“Mother and Child”) and community (“Village Dance”) is included here, visitors will find only one work by Rivera, who, as Witte curator of collections Amy Fulkerson points out, has a long history with the museum.

“The Witte was the first venue in San Antonio to exhibit Rivera, in 1927, so it's a nice connection to our history,” Fulkerson says.

Rivera's 1932 lithograph “The Teacher — The Fruits of School,” which looks like a pencil drawing at first glance, is a sensual work that “employs the classicizing style of Italian Renaissance fresco alongside the smooth elongated forms favored by the Cubists,” Moreno writes in exhibition materials. “His symbolic image valorizes popular education and implies it is planting the seeds of the nation's future.”

Photography occupies a longstanding and important niche in the history of Mexican art, and no exhibition chronicling the 20th century would be complete without Manuel Alvarez Bravo, the influential photographer whose work is such an important window on the world, as well as being a bridge from the past to the present.

The images here, which span the years from 1927 to 1972, capture a sense of Mexican daily life that only Alvarez Bravo could, with his unique vision. His '30s portrait of Frida Kahlo is absolutely majestic.

The most striking photographs in “Miradas,” however, are by Graciela Iturbide, born in 1942, who apprenticed with Alvarez Bravo — and perhaps has surpassed the master. Iturbide's lens found one of Mexico's most iconic images, which she titled “Mujer angel (Angel Woman),” depicting a young woman navigating the Sonora Desert, presumably heading north, with a boom box in her hand. It compresses so much political information into a single image.

The Chicano movement is epitomized in the work of Judithe Hernandez. The pioneering artist is represented here by a strong 2008 pastel on paper work from her Manos de sangre series.

“Red Hand, Bloody Hand, Hand of Oppression” encompasses nine small facial portraits of women in a grid format, as if they are caged or jailed. Bloody handprints are splashed on eyes, mouths, cheeks or necks, reflecting the artist's concern about the abuse of women. It's difficult not to think of the hundreds mysteriously murdered along the border when contemplating Hernandez's disturbing piece.

Many other works are worth discussing in “Miradas”: “There truly is something for everyone in ‘Miradas,'” Fulkerson says.

Can't miss works include a suite of prints by Luis Jiménez (check out “Bronco I”; nobody captured equine fury like Jiménez); the surreal folk narrative paintings of Alejandro Colunga, leader of the Nueva Mexicanidad movement; the “Rodeo Drive” series of Cibachrome prints dealing with rampant consumerism and the inequity of wealth by Los Angeles artist Anthony Hernandez; thesymbolic paintings of self-taught artistRaymundo Andrade, who holds degrees in medicine and history, a fact that obviously influences his allegorical work; and Ricardo Rendon's large multimedia installation “Trabajo Diario (Daily Work),” which takes up two walls and features 31 consecutive front pages of the tabloid periodical La Jornada from August 2007.

“Miradas” visitors can't fail to linger over Javier Chavira's “El guerrero (Warrior),” which dominates the entry foyer to the exhibition, and in many ways embodies the dominant themes of the show: Chavira is a young Mexican American artist educated in the Midwest who draws on traditional Mexican sources of imagery, including indigenous sculpture, the Catholic Church and native folk art.

“In addition to producing drawings and paintings,” Moreno says, “Chavira has executed murals on schools and other buildings. ‘The Warrior,' with its architectonically rendered, monumentally proportioned head of an indigenous male, is reminiscent of Chavira's murals.”

A Doctor in medicine and a Doctor in letters and history, Raymundo Andrade fuses a unique academic background with his art. His canvases are veiled in a delicate sense of nostalgia, and warm muted tones seem to further suspend his images in timeless reverie. His works clearly pay tribute to both the natIve and Spanish cultures that are such a part of Mexico’s vast cultural history. Spiritual, cultural, and natural richness and fertility are themes that pervade the themes of this artist. His works have been exhibited extensively in California, Arizona, Washington, and Mexico.

A physician, philosopher, and artist with an extensive background of exhibitions in Mexico, the U.S., and Canada.

“I don’t like making statements about my work, because I don’t paint with a concept or a story as a starting point. I start with an image, so it is sometimes difficult to put into words. They (my paintings) are images that I like, it’s like the sunset, it’s something that strikes you.”

Raymundo appears to be a man drawn to the great mysteries of the human condition. His motivations and themes lead Raymundo to follow the school of the great masters. “If I used a brighter palette, or a hyper-realistic approach, my paintings wouldn’t come across the same”

RAYMUNDO ANDRADE

WITTE MUSEUM USA

San Antonio, .TX USA

MySA San Antonio´s Home page web Escrito por Steve Bennet

“Miradas” runs through Aug. 21 at the Witte Museum, 3801 Broadway.Arts & Culture

'Miradas' reveals how Mexican artists confronted modernity after Revolution

By Steve Bennett [email protected]

Javier Chavira's painting "El guerrero (The Warrior)" is featured in "Miradas: Mexican Art From the Bank of America Collection," a survey of 80 years of Mexican art since the revolution.

The Witte Museum marked the centennial of the Mexican Revolution last year with its multifaceted exhibition “1910: A Revolution Across Borders.” Now the venerable institution examines the artistic legacy of that earth-shattering rip in society's fabric with a seismic summer show that traces the development of Mexican art over the past 80 years in some 100 works.

“Miradas: Mexican Art From the Bank of America Collection” features paintings, prints and photography by 32 artists, including Diego Rivera, Manuel Alvarez Bravo, Graciela Iturbide and Rufino Tamayo, as well as contemporary artists such as Alejandro Colunga, Judithe Hernandez and Luis Jiménez.

“The ‘Revolution' show was very gritty,” says Marise McDermott, Witte president. “It really captured the violence of those times. This one explores the explosion of art across the U.S.-Mexico border.”

According to Cesáreo Moreno, chief curator and visual director at the National Museum of Mexican Art in Chicago, a furor of post-Revolution nationalism fueled the engines of creativity as Mexican artists rediscovered their country's past and peered ahead into its future.

“At the close of the war, an era of peace was ushered in gradually, with a different political order, a strong sense of nationalism — known as Mexicanidad (Mexican-ness) — and newfound social goals,” says Moreno, organizer of “Miradas,” a touring show culled from one of the country's strongest corporate collections. “Artists sought to develop an artistic language that could convey their sense of modernity in an increasingly industrialized world.”

Among the outlets of expression was a cultural movement known as Indigenismo (Indigenism or Indianism), Moreno says, pointing to “Miradas” paintings by Jean Charlot, a Zapotec mestizo born in Paris in 1898, and Guatemala native Carlos Mérida's series of lithographs reimagining the creation myths of the Popol Vuh.

“Artists and writers who participated in this movement explored their national heritage and proudly included in their work aspects of ancient Mesoamerican culture,” he says.

The Mexican mural movement emerged from the Revolution as well, and Los Tres Grandes (The Three Giants) — Diego Rivera, José Clemente Orozco and David Alfaro Siqueiros — became Mexico's artistic ambassadors, global beacons who championed indigenous culture and the rights of the common man, even as they adopted and adapted international avant garde theories and methods.

Although a meditative suite of later (1968) Siqueiros lithographs dealing with family (“Mother and Child”) and community (“Village Dance”) is included here, visitors will find only one work by Rivera, who, as Witte curator of collections Amy Fulkerson points out, has a long history with the museum.

“The Witte was the first venue in San Antonio to exhibit Rivera, in 1927, so it's a nice connection to our history,” Fulkerson says.

Rivera's 1932 lithograph “The Teacher — The Fruits of School,” which looks like a pencil drawing at first glance, is a sensual work that “employs the classicizing style of Italian Renaissance fresco alongside the smooth elongated forms favored by the Cubists,” Moreno writes in exhibition materials. “His symbolic image valorizes popular education and implies it is planting the seeds of the nation's future.”

Photography occupies a longstanding and important niche in the history of Mexican art, and no exhibition chronicling the 20th century would be complete without Manuel Alvarez Bravo, the influential photographer whose work is such an important window on the world, as well as being a bridge from the past to the present.

The images here, which span the years from 1927 to 1972, capture a sense of Mexican daily life that only Alvarez Bravo could, with his unique vision. His '30s portrait of Frida Kahlo is absolutely majestic.

The most striking photographs in “Miradas,” however, are by Graciela Iturbide, born in 1942, who apprenticed with Alvarez Bravo — and perhaps has surpassed the master. Iturbide's lens found one of Mexico's most iconic images, which she titled “Mujer angel (Angel Woman),” depicting a young woman navigating the Sonora Desert, presumably heading north, with a boom box in her hand. It compresses so much political information into a single image.

The Chicano movement is epitomized in the work of Judithe Hernandez. The pioneering artist is represented here by a strong 2008 pastel on paper work from her Manos de sangre series.

“Red Hand, Bloody Hand, Hand of Oppression” encompasses nine small facial portraits of women in a grid format, as if they are caged or jailed. Bloody handprints are splashed on eyes, mouths, cheeks or necks, reflecting the artist's concern about the abuse of women. It's difficult not to think of the hundreds mysteriously murdered along the border when contemplating Hernandez's disturbing piece.

Many other works are worth discussing in “Miradas”: “There truly is something for everyone in ‘Miradas,'” Fulkerson says.

Can't miss works include a suite of prints by Luis Jiménez (check out “Bronco I”; nobody captured equine fury like Jiménez); the surreal folk narrative paintings of Alejandro Colunga, leader of the Nueva Mexicanidad movement; the “Rodeo Drive” series of Cibachrome prints dealing with rampant consumerism and the inequity of wealth by Los Angeles artist Anthony Hernandez; thesymbolic paintings of self-taught artistRaymundo Andrade, who holds degrees in medicine and history, a fact that obviously influences his allegorical work; and Ricardo Rendon's large multimedia installation “Trabajo Diario (Daily Work),” which takes up two walls and features 31 consecutive front pages of the tabloid periodical La Jornada from August 2007.

“Miradas” visitors can't fail to linger over Javier Chavira's “El guerrero (Warrior),” which dominates the entry foyer to the exhibition, and in many ways embodies the dominant themes of the show: Chavira is a young Mexican American artist educated in the Midwest who draws on traditional Mexican sources of imagery, including indigenous sculpture, the Catholic Church and native folk art.

“In addition to producing drawings and paintings,” Moreno says, “Chavira has executed murals on schools and other buildings. ‘The Warrior,' with its architectonically rendered, monumentally proportioned head of an indigenous male, is reminiscent of Chavira's murals.”